July 25, 2002

In the distance, a spotlight on top of the ultramodern Shanghai Grand Theater dances a wide path through the night. Other buildings flash staccato laser-light bursts while others pulse steady multicolored rainbows into the black sky. Far below, the city streets teem with activity long after dark. Our guide Ellen explains “it’s such a different culture here in Shanghai.”

Like many of Shanghais early-30s crowd, Ellen is grateful for her steady job as an office manager in an emerging technology company. For many of Ellen’s generation, Shanghai represents their future the place where dreams come true; where their ship will surely come in. Nothing else matters.

But to Ellen, who turns from the office window and closes the blinds, the scene below reminds her how far she has come. Before, I wanted it all. I wanted wealth and material things, just like all these other people running around down there, Ellen says. But now, “I want God. God is first.” Her faith and values are not widely shared in this flourishing city of nearly 28 million.

More than in any other part of China, early Shanghai grew out of foreign influence and corruption. After the British strong-armed China into opening its ports for trade in 1842, America and France rushed to claim their share of the spoils.

Soon, each country had exacted its own autonomous territory in Shanghai, exempt from Chinese law and interference. Once just a marshy fishing village, Shanghai had become the place to be.

As the only port in the world not requiring an entry visa in the early 1900s, Shanghai drew people from all walks of life adventurers, crooks, missionaries, opium dealers, Jews fleeing persecution from the strengthening Nazi boot, gamblers and American and European elite seeking fun and fortune.

Not all of Shanghais foreign population embraced the extravagance, however. As one foreign missionary surmised at the time: “If God lets Shanghai endure, He owes an apology to Sodom and Gomorrah.”

For decades, Shanghai and its native peoples were used and abused by the wealthy and crooked alike staging their theatrical decadence’s. Cabarets, horse-racing tracks, theaters, brothels and a glitzy night life masked the reality of millions of Chinese eking out lives as coolies and servants.

As with the entire Chinese nation, the communist party expelled foreign influence from the city when it rose to power in 1949. For a full 50 years, the historical Shanghai sat like a dusty, forgotten artifact, supplanted by the drab conformity of communism and atheism.

But in 1990 China’s leaders, realizing the need to relax their isolationist and socialist grip, opened the country up albeit slowly to capitalism. Shanghai, cash cow of the past, was to be an economic experiment. She would be the model city of modernization and commerce. She would seduce foreign investors and be a Mecca for multinational businesses.

In the 12 years since, the building boom has not paused for a breath. Shanghais skyline bristles with skyscrapers and construction crews work day and night filling the horizon with more. At 1,380 feet, the world’s third-highest building the “Jin Mao Tower” stands 88 stories above futuristic, glass-sheathed office buildings of the Pudong development district.

Visitors describe the city as a Paris, New York City and Hong Kong blended together. Shanghais new streets built broad with wide, Parisian-style walkways in many parts of the city are crowded with people.

In a way, the city is now a melting pot of China. Although there are the people who call themselves Shanghainese and proudly speak a unique dialect, millions of residents are Chinese who have come to make it in the big city.

This truly is the “Mouth of the Dragon.” Everyone from China’s countryside is trying to get here; all the people from here are trying to get out into the world; and the rest of the world is trying to get into China through here, says one local Chinese characterizing Shanghais prominence. At any given time, Shanghai supports up to 4 million migrants drawn to the big city for jobs, looking for the big break.

At both of the city’s train stations, thousands of out-of-towners wait for job brokers to offer work anything for a wage. Until then, they sleep, eat, gamble and wait on the sidewalk, the grain sack containing their belongings easily identifying them as a transplant from the countryside.

As contemporary, independent and wealthy as Shanghai may appear, its luster has come with a price. Many of its people, especially the younger generation who have not experienced the same hardships as their parents and grandparents, are lost in indifference in their self-serving pursuit of wealth, materialistic gain and worldly enjoyment.

For so many young people in this city, money is their god, Ellen says. They think it will satisfy their needs, but their hearts are empty. It’s vanity. Could it be that history will repeat itself in Shanghai? Christians, international or Chinese, hope not.

Shanghai is a proving ground for the rest of China, Ellen explains. If it flies in here, it’s got validity. The Chinese see Shanghai like the Big Apple, if I can make it there, I’ll make it anywhere.

And while that is the philosophy pertaining to employment and financial gain, Ellen also believes this is how Christianity can spread through China. If the gospel catches on here, it will spread throughout China. There’s no doubt about it, she says.

Frank Owens, another Christian working to impact Shanghai with the gospel, characterizes the city’s glitz, shopping malls, designer clothes and European architecture as a thin veneer covering the reality. Underneath lays the truth: “millions of unhappy and empty people lost without Christ.”

A task of this magnitude has to be a God thing, Owens says. I take comfort in that. Because we have such overwhelming challenges as we look to reach this city, our strategy has to match those challenges.

Owens and Ellen have seen pockets of spiritual activity in the city, evidence that God is working here. Sharing Christ in this city demands a different approach to reach this materialistic, atheistic society. There is no concept or belief in a supreme being, and people have no interest in talking about what will happen after it’s over. It’s all about the “here and now.”

Ask any native Shanghainese about the city’s future and the answer is nearly always the same she is a city being driven by the morally depraved, and that will drive her into the ground.

Like many urban Chinese, James uses a Western nickname. Sitting in a centuries-old traditional tea house in the ancient section of Shanghai, James wonders how long his native city will prosper. Just blocks away, huge sections of the ancient town homes to generations of Shanghainese are being razed for luxurious condominiums. Modernization is displacing thousands.

As he watches tea leaves float to the bottom of his glass of steaming chrysanthemum tea, James scoffs at the city’s future. Young people today are lazy. They know nothing of work; says James, who owns a pearl shop. I knew poor, so I know what it takes to make a good life. Kids now just take and take.

While he agrees that morals and a belief in God would help, who has the time? Look, I’m a Christian, he says, pulling out a hidden necklace which holds a jade and gold cross. Well, my parents were, so I am one, too. But no time for church, must work he grins, heading back to his pearl shop. Maybe my son will go to church.

How do you even begin to formulate a strategy for reaching a city that possesses this kind of mentality? Ellen asks. Through partnerships with local Christians like Mr. Zhou (pronounced Joe), Ellen and Owens know the city will be reached when the hearts of the people are ready.

Materialism and money are the biggest problems in Shanghai, says Zhou, who for 12 years has been a house-church leader in Shanghai. Too many are pursuing the world. The spiritual eyes of the people are blind. They do not know the joy of obedience.

Moving around to various locations to avoid detection, Zhou ministers to approximately 300 people who meet in seven different groups around the city. In the 12 years he has served as a shepherd in Shanghai, he has seen the house-church movement quadruple in growth.

God can use a corrupt system to prepare hearts. He will open the hearts of the Chinese people. This city and system is preparing China to come to God. And then, Zhou earnestly says, the movement of God will allow Shanghai to be a launching pad.

Owens agrees. Before a great church-planting movement starts in Shanghai, there must be a deep spiritual movement, he adds. Without it, we go through the motions and nothing happens.

Thinking of her own salvation experience, Ellen agrees. Shanghainese, if they have a chance to hear the gospel, will begin to compare it against their lives. And words are good, but our actions must also be a witness of the Father. I want what I do to please the Father, and help take away the world’s doubts. So many depend on their worldly environment. We must be different.

God will make a way for this city to know Him, she says. He is one who plants and allows the seeds to grow. I know that because He did that in my life.

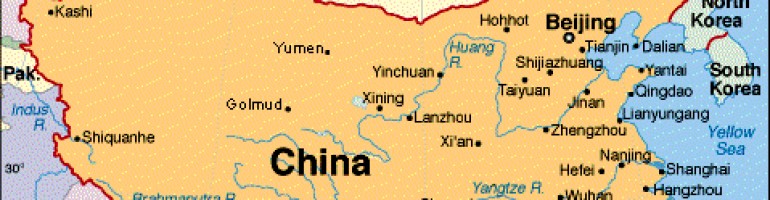

The Shanghainese have a proud saying about the prosperity and future of their grand city: “If you want to see the China of yesterday, go to Xian (the ancient capital). If you want to see the China of today, go to Beijing. To see the China of tomorrow, go to Shanghai.”

It is the prayer of people like Zhou, Ellen and Owens that as the people do come, they would, indeed, be greeted by the future of China, a future resting only in the hope of Jesus Christ. The son of China missionaries, Dan Williams toke us to visit a piece of Baptist history in Shanghai.

Today’s Shanghai visitor walking north along the famous Bund (Zhongshan Dong-Lu), the Huangpu River’s waterfront, might look to the right at the busy harbor traffic or at the dominating Oriental Pearl Tower on the Pudong side. The view to the stroller’s left, also visible to a passenger aboard a cruise ship moored at the nearby International Passenger Terminal, would include several low buildings on a parallel street only one block away from the Bund. The most noticeable of these is a nine-story reddish building with light blue sunshades over each window. This is the “True Light Building”, completed for and by Southern Baptists 70 years ago in 1931, at 209 Yuen Ming Yuen-Lu.

The building was named for “The True Light”, a periodical published by the China Baptist Publication Society that occupied the entire ground floor with its extensive printing presses and a retail book store. Sunday school lessons, Bible tracts and other Baptist literature were printed, all in Chinese of course, on the premises.

Through various China emergencies, the Japanese takeover during World War II and the Peoples Republic of China government confiscation in 1949, the Southern Baptists “True Light Building” name has continued unchanged and the four golden Chinese characters over the main entrance unaltered. Reading from left to right, they are zheng (true), guang (light), da (large), and lou (structure). Since the building’s 1931 dedication, however, China’s history and that of Baptist and other missionary movements in China has changed enormously.

To rewind to the 1930s, Foreign Mission Board (now the International Mission Board) work in China functioned in four geographic missions South China, Central China, North China and Interior China. Southern Baptist missionaries lived and worked in one of the two to nine city locations or stations included in each mission.

As China mission’s treasurer, my father, James T. Williams, a graduate of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, was responsible to the board for all banking, transportation, property management, payroll, legal, governmental compliance and other miscellaneous operating activities necessary to support the work of all Southern Baptist missionaries in China. My mother, Laurie Williams, taught high-school level classes at Southern Baptists Ming Jang Academy and Eliza Yates Academy and worked in Chinese churches.

Because he spoke both Cantonese and Mandarin dialects, he also preached frequently at the Cantonese services of one of the Baptist churches in Shanghai. Details of his job seemed endless, and his working hours were long. On behalf of the board, he oversaw the planning and construction of the True Light Building, with all of the architectural and construction decisions.

Mission offices included temporary space for missionaries visiting Shanghai and, later, an office for Dr. M. Theron Rankin, FMB secretary for the Orient. From that seventh floor elevation, visiting MK’s (missionary kids) occasionally launched folded paper gliders with hopes that the flight would carry them all the way to the Huangpu River.

Events moved swiftly, as Japan began to accelerate its expansion toward its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Each move affected the Southern Baptist Convention’s China missions. In 1931, Japan conquered Manchuria, which placed the North China Mission station of Harbin into the new puppet nation of Manchukuo, totally controlled by Japan.

In early 1932, Japanese Naval Landing Forces landed near Shanghai and attacked China’s brave but out-gunned and out equipped 19th Route Army. During this incident and after the beginning of Japan’s war on China, which began in mid 1937, Baptist and other missionaries stationed in some Central China and North China locations, not knowing the ultimate extent of hostilities, moved temporarily to the relative safety of the then French Concession and International Settlement Zones in Shanghai, in which the True Light Building was located.

As had happened in 1927, during Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Government takeover of China, housing, school and other emergency arrangements were made for the displaced missionaries in Shanghai during what was hoped to be a temporary war.

By early 1941, at the board’s recommendation, most Southern Baptist women and children began to return to the United States. Missionaries, who remained after Pearl Harbor, mostly men, were interned by the Japanese in Shanghai, Hong Kong, Manila and Chefoo (now Yantai) and Weihsien in North China.

A few Southern Baptist missionaries, situated far to the west in Free China and beyond Japan’s reach, functioned relatively undisturbed. During World War II, the True Light Building was visited regularly by Chinese Baptist workers and was left relatively intact by the Japanese occupation forces.

Shortly after V-J Day, after participating with my Marine Corps combat division in the Iwo Jima and earlier Pacific island invasions, I arrived in Shanghai as a U.S. Marine Corps second lieutenant en route to postwar Japanese surrender, prisoner release and peacekeeping duties in North China.

At the True Light Building, I met the manager of the Baptist publication operations, old friend C. Y. Ting, and his Chinese fellow workers, who had already initiated a cleanup and survey of the building. It was a joyful reunion. A few months later, in Honolulu, I visited with China missionary friends doing Baptist work in Hawaii for the duration, and all asked about the True Light Building as well as for all other details I could provide on the status of Chinese Baptist workers and churches and the likelihood of prompt resumption of Southern Baptist missionary activity in China.

It resumed and grew, with mounting uncertainties, until 1949 when the People’s Liberation Army achieved total control of China. The True Light Building and all mission church, school, hospital, residence and other properties were confiscated by the People’s Republic of China and its provincial and other subordinate governments, which effectively own them today. Termination in 1949, until further notice, of Baptist witnessing in China begun by John and Henrietta Shuck in Macau in 1836, seemed to most missionaries the culmination of work interruptions over the years.

I was impressed by what I saw of that work through the years. For safety considerations, women’s work was frequently delayed because they were ordered to move from areas deemed temporarily dangerous. Still every missionary woman, single or married, was a full-fledged missionary with a commitment to expand the kingdom of God, same as men missionaries.

But I was most impressed not only to observe the mutual help and joint prayers for spiritual guidance among missionaries and their Chinese co-workers as a single family, but also their total commitment to their original calls to spread the gospel, a determination as important as maintaining life on earth.

Many missionaries chose to ignore risks and contrary advice and remain at or go to mission decidedly dangerous locations, exhibiting a bravery and self-sacrifice similar to that I saw during battlefield combat. At mealtime and other prayers at our home, my father would pray especially for journeying mercies for a particular returning missionary. The common decision of those totally dedicated missionaries was the same as that attributed to acclaimed Southern Baptist medical missionary Bill Wallace, I will stay as long as I am able to serve.

The True Light Building is fully operational today and is occupied by Chinese commercial tenants. It has been designated by the Shanghai city government as a municipal preserved building, a historical structure, and bears that plaque at the building entrance. The occupants of my father’s former office, Room 703-5, are most hospitable and seem genuinely interested, as most Chinese are, in former residents and friends of China.

As expressed in John 1:9 “The true light that gives light to everyone was coming into the world” continues to exist now and into the future.